By Michael Alison Chandler,

For decades, the prevailing wisdom in education was that high self-esteem would lead to high achievement. The theory led to an avalanche of daily affirmations, awards ceremonies and attendance certificates — but few, if any, academic gains.

Now, an increasing number of teachers are weaning themselves from what some call empty praise. Drawing on psychology and brain research, these educators aim to articulate a more precise, and scientific, vocabulary for praise that will push children to work through mistakes and take on more challenging assignments. Consider teacher Shar Hellie’s new approach in Montgomery County.

To get students through the shaky first steps of Spanish grammar, Hellie spent many years trying to boost their confidence. If someone couldn’t answer a question easily, she would coach him, whisper the first few words, then follow up with a booming “¡Muy bien!”

To get students through the shaky first steps of Spanish grammar, Hellie spent many years trying to boost their confidence. If someone couldn’t answer a question easily, she would coach him, whisper the first few words, then follow up with a booming “¡Muy bien!”

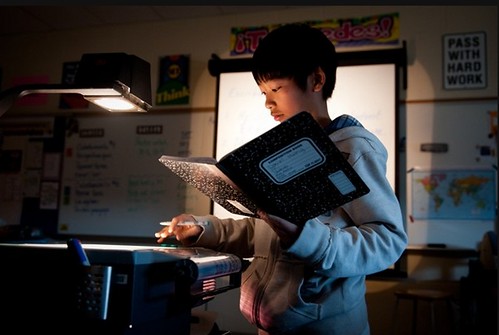

But on a January morning at Rocky Hill Middle School in Clarksburg, the smiling grandmother gave nothing away. One seventh-grade boy returned to the overhead projector three times to rewrite a sentence, hesitating each time, while his classmates squirmed in silence.

“You like that?” Hellie asked when he settled on an answer. He nodded. Finally, she beamed and praised the progress he was making — in his cerebral cortex.

“You have a whole different set of neurons popping up there!” she told him.

A growing body of research over three decades shows that easy, unearned praise does not help students but instead interferes with significant learning opportunities. As schools ratchet up academic standards for all students, new buzzwords are “persistence,” “risk-taking” and “resilience” — each implying more sweat and strain than fuzzy, warm feelings.

“We used to think we could hand children self-esteem on a platter,” Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck said. “That has backfired.”

Dweck’s studies, embraced in Montgomery schools and elsewhere, have found that praising children for intelligence — “You’re so clever!” — also backfires. In study after study, children rewarded for being smart become more likely to shy away from hard assignments that might tarnish their star reputations.

But children praised for trying hard or taking risks tend to enjoy challenges and find greater success. Children also perform better in the long term when they believe that their intellect is not a birthright but something that grows and develops as they learn new things.

Brain imaging shows how this is true, how connections between nerve cells in the cortex multiply and grow stronger as people learn and practice new skills. This bit of science has proved to be motivating to struggling students because it gives them a sense of control over their success.

It’s also helpful for students on an accelerated track, the ones often told how “smart” they are, who are vulnerable to coasting or easily frustrated when they don’t succeed.

That’s how teachers at Rocky Hill Middle started talking about “neuroplasticity” and “dendritic branching” during training sessions. They also started the school year by giving all 1,100 students a mini-course in brain development.